Read the introduction and see the full album list here.

Jazz standards are unpopular these days, for good reasons (high schoolers pointing their trumpets in The Real Book at the Berklee Jazz Festival) and bad (tradition versus innovation, blah blah blah, see my previous post). Myself, I’m against jazz standards for two reasons: they blind us to the great tunes of today which should share equal billing (and fake-booking, if you’re into that sort of thing), and they dull the vitality of the ”standards” themselves.

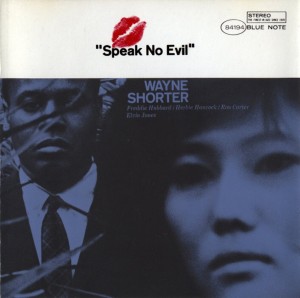

Wayne Shorter is in the news recently for his newest record, and return to Blue Note – Without A Net. Writing my review for Nextbop inspired me to go back to the source of my love for Wayne – his awe-inspiring Speak No Evil, recorded during his first stunt for Blue Note in 1964. At least half of its six tunes are considered jazz standards, but looking back from 2013 – almost fifty years later – Speak No Evil is far from dulled.

It’s an equilibrium record. You know what I mean – the kind of record where everything hangs suspended in a perfect balance. The slightest tap on either side of the scale, we feel, would disrupt the whole thing.

Nothing taps Speak No Evil.

It was recorded by a quintet perfectly matched; more perfectly, it seems to me, than any other of the records made in 1964-1966 by this almost incestuously promiscuous group of musicians, almost all from the bands of either Miles or Coltrane. Maiden Voyage, Lifetime, Fuchsia Swing Song, The Soothsayer…

That last record provides a useful counterpoint in Tony Williams’s drums. The Soothsayer (and all the records made by or with Wayne Shorter that feature Williams) is an uneasy record, a jittery, sharply angled record. It contains beautiful music – there’s no denying the beauty of its music – but it never seems to settle into any identifiable space.

Speak No Evil lives in its own world, and Elvin Jones is its master carpenter. Speak No Evil is very much an ensemble record, but it is also very much an Elvin Jones record. Would the dark energy of ”Dance Cadaverous” (a criminally underplayed tune) have been possible without the solidly hollow sound of Jones’s tom-toms at its beginning, or the crackle of his snare? Would the maelstrom of swing that envelops the title track exist without Elvin’s seemingly eight-armed contribution?

He doesn’t do it by himself, of course; just as the lead carpenter doesn’t build the house by himself, Elvin’s energy and momentum are beautifully complemented by Wayne’s crew on Speak No Evil. Herbie Hancock plays one of his most delicately powerful solos on ”Infant Eyes,” and lays down a muscular, bluesy passage on ”Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum.”

There’s a particular face I make when I hear ”Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum.” It’s the face I often felt myself make at certain glorious moments when playing music myself, on the bandstand; the best recorded music brings me those same feelings of being on the brink, teetering on the edge of something wonderful. My whole being tenses as the music reaches the edge of the creative cliff, and there is pure joy as the music takes off, rather than drops.

This record is that cliff. Every melody, every solo, contains that moment of tension, stretched and drawn out like a rubber band, then snapped back into what, by the time it’s over, seems inevitable. The depth of field is incredible: to listen to ”Dance Cadaverous” or the rawness of ”Witch Hunt” on tinny speakers is a crime.

Perhaps that’s the real problem with jazz standards. ”Witch Hunt,” in particular, has become a standard jam session tune for young musicians thanks to books like The Real Book. But those charts are just another version of tinny speakers. A chart could never capture the urgency with which these melodies are played, the immediacy of their existence on vinyl. As with Lee Morgan’s best tunes (”Party Time” is one), it seems impossible that the melodies on Speak No Evil could ever have been written down, even by their composer; there is a seamless interaction between written and improvised melody here.

I’ve mentioned ”Dance Cadaverous” a few times already. When you close this browser window, pause a moment before going to Twitter or Facebook or Buzzfeed or whatever your plans may have been; open iTunes and plug in your best speakers, or better yet walk to the turntable and take Speak No Evil out of its sleeve; and listen to ”Dance Cadaverous.” Do not speak. Just listen. The read this essay again, and maybe then, you will see what I can barely hint at here; because the truth of this music is only found in this music.